Aspirational Inflation Rates and the CPI

Everything is getting more expensive. What prices you care about are the prices that matter most.

The “I” in CPI does not stand for inflation.

Although often referenced interchangeably as inflation, in reality the Consumer Price Index (CPI) is an attempt at measuring a subset of price data within the economy. The CPI measures the weighted average inflation rate for a market basket of goods and services, within certain limitations and margins of error.

That “basket” includes food, clothing, shelter, energy, and transportation, with each component being assigned a weight based on what people typically buy. Shelter currently accounts for about 33%, food about 13%, and transportation about 5.6%, and over the course of a year as some prices rise and others fall, the CPI delivers an average rate of change for the whole basket. Over the past year in the US, it was 7.5%.

The CPI’s inherent limitation is that it samples only on a subset of prices, weighted in a particular way, rather than all prices. Ultimately, what is chosen to be put in that basket, the weighting, and the sampling method will determine what the CPI will be for any given month.

Since changing items in the basket and their weighting would yield a completely different inflation rate, the ultimate question for measuring inflation is:

What should be in the basket?

Aspirational Price Index

In a conversation with Preston Pysh, Microstrategy CEO Michael Saylor offered an alternative perspective on inflation.

The prices that people should care about are the prices of things that they want, not what they buy.

To illustrate his point, Saylor pointed out two differing aspirational directions:

For a person who seeks to live in his parents’ basement, drink beer, watch Netflix and eat junk food, the prices he cares most about are the prices of beer, Netflix subscriptions and Cheetos. Price movements of goods and services beyond the scope of those aspirations carry little to no relevance, as they do not affect his desired lifestyle.

For the person who seeks a better quality of life, the prices he cares most about would be completely different...

If he seeks to own a house within a commutable distance of a nice city, then prime real estate prices in major urban markets are relevant.

If he seeks to earn a high wage, then the prices of higher education at top universities are relevant.

If he seeks to be healthy, then the price of organic food, quality healthcare, and leisure time to exercise are relevant.

If he seeks to earn passive income, then the price of dividend-paying stocks, rental properties, and high-yielding bonds are relevant.

If he seeks to be wealthy, then the price of scarce, real-yielding, and appreciating assets are relevant.

Essentially Michael Saylor’s point is that inflation affects people on a deeply personal level, as price changes represent real impediments to fulfilling aspirational goals.

Everyone has their own personal inflation rate, which is the changes in prices of goods and services that they care most about. The degree to which their personal basket of prices overlaps with the CPI’s basket is the degree to which the CPI carries relevance.

By focusing on the CPI as the main indicator for inflation, the inflation conversation is skewed towards highlighting the prices of things needed to survive, rather than thrive. The monthly CPI numbers paint a picture of price changes in consumables, depreciating assets, and a general lifestyle lacking in social mobility.

Although the CPI increase of 7.5% this year in the US reflects a substantial increase in the cost of living, the cost of improving one’s lifestyle has gone up much more. Scarce assets, real-yielding assets, premium services, and desirable goods have all inflated by double-digit percentages. Owning a share of the S&P 500 index costs 14% more, owning dividend-paying stocks costs 11% more, owning property in the most desirable locations costs 10%-25% more.

Although the CPI is up by 7.5%, anyone who aspires to be more than a consumer experienced an inflation rate in the double-digits.

Price Divergence

The divergence between consumer prices and aspirational prices can be largely attributable to supply scarcity.

As more people demand goods and services, producers respond by delivering more supply. Any increases in demand for cars, TVs, and cheeseburgers can be met with more of those goods being produced, as factories, supply chains, and retail outlets can ramp up production.

However, any increases in demand for prime real estate, blue chip stocks, and Ivy-League admission will not be met with a similar increase in supply. These highly-valued, aspirational goods and services have largely inelastic supplies, meaning they are incapable of readily responding to changes in demand pressures.

It is easier to create more bags of Cheetos than it is to create more prime real estate.

A broad increase in demand for all goods and services would affect prices differently, depending on supply elasticity. Scarcity, or the inability of supply to be increased, means that aspirational goods have the capacity to experience price inflation at a faster pace than consumable goods.

This divergence of prices is of particular concern due to the accelerated rate of money printing in recent years. Whether in the form of stimulus checks, quantitative easing, or any type of unfunded money supply increase, new money is being created out of thin air as a means of supporting banks, businesses, and citizens.

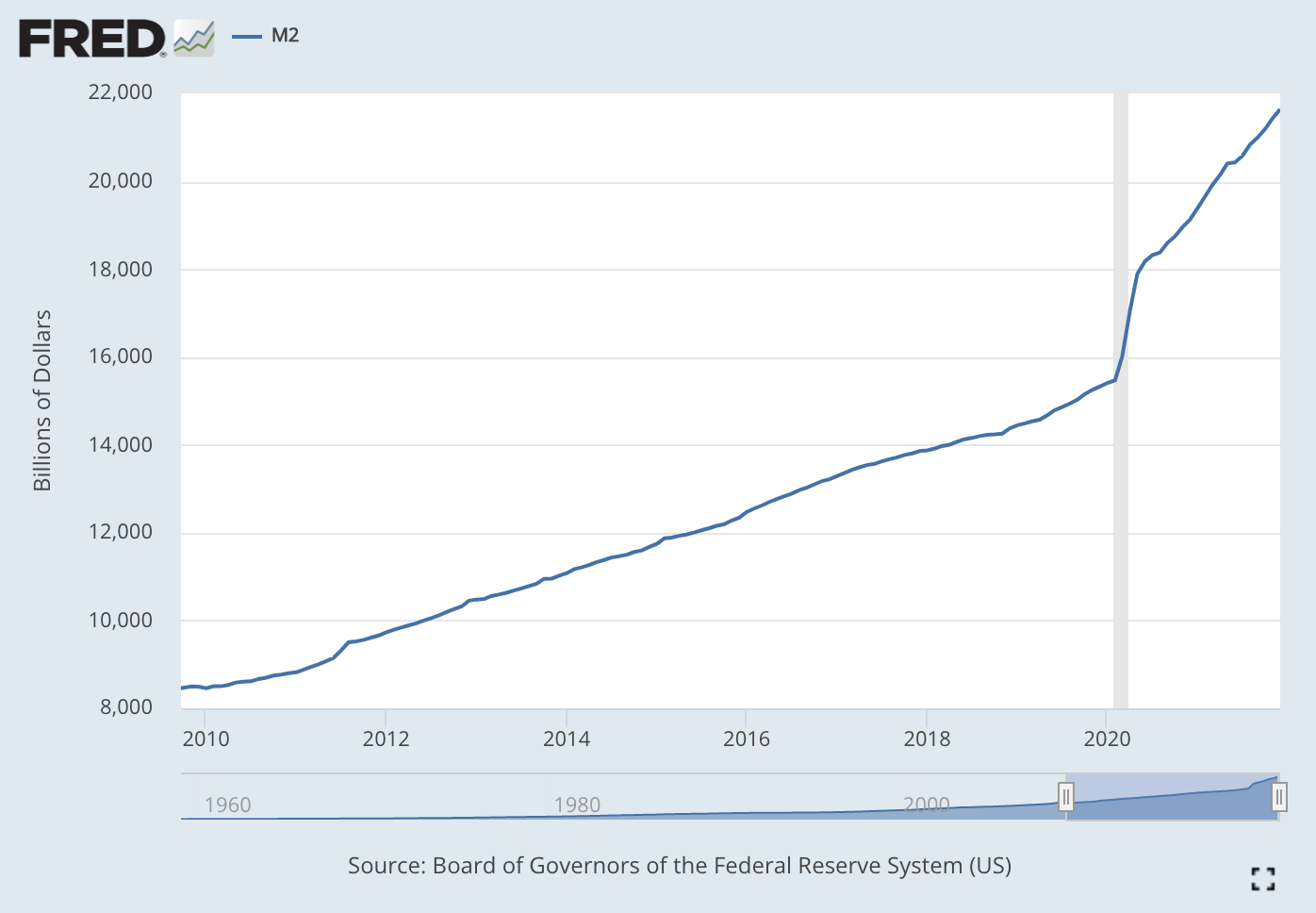

The M2 money supply has grown by 40% in the past 2 years, meaning more liquidity, cheaper borrowing, and even free cash being handed out as a way to stimulate economic activity through providing sources of demand pressure. This new, cheap influx of money is fostering inflationary pressures by adding demand in pursuit of existing supplies, but due to differing supply constraints across goods and services, price increases are not uniform.

Supply-constrained assets are inflating faster than supply-flexible assets.

In some cases, the availability of cheap borrowing and liquidity has even allowed companies to offer share buyback programs, thereby decreasing the supply of their shares. Since the start of COVID, there has been a 6.3% decrease in total Apple shares outstanding, coinciding with a doubling of the share price.

Although prices of food, clothing, and cars have all increased in the past two years, due in part to increased demand pressures, those price increases fall short of those in prime real estate and stocks.

While rapid price increases may be good news for the owners of scarce assets, for everyone else it represents impediments to their aspirations.

Retirement

Every consumer, regardless of their lifestyle aspirations, must find a way to provide for themselves after they retire.

Although the CPI contains food, shelter, transportation, and various monthly expenses, there is no component tracking the price of a retirement product, something that all adults should be buying month to month.

What is the price of such a retirement product?

It is the price of a market basket of goods that offers a multi-decade, low-risk return, capable of yielding sufficient cash flow to support a given retiree. Historically, that meant a diversified portfolio, which steadily decreased its risk exposure over time by allocating more towards bonds and less towards stocks as the individual approached retirement.

Previous generations of retirees could earn double-digit percentage yields on low-risk government debt, however, the current US 10-year treasury yields less than 2%, well below any measure of inflation. While holding a bond for 10 years is a low-risk way to increase nominal wealth by 2%, the fact that the cost of living is increasing multiple times faster than 2% means purchasing power is decreasing. Allocating any investment capital towards low-risk bonds has become a contractual agreement to lose real wealth over time.

Funding retirement with the equivalent low-risk portfolio enjoyed by previous generations has become prohibitively expensive. Prospective retirees are being pushed further into ever-riskier investment portfolios, lest they risk losing real wealth. When investments are returning less than inflation, then the prospect of retirement is getting more expensive and further away.

If conventional wisdom is to put away 15% of your monthly paycheck towards retirement, it stands to reason that the price of retirement should be included in inflation measurements, and account for 15% of any reasonable person’s basket.

Individualized Baskets

Price inflation is like chasing a plastic bag caught in the wind. In order to catch the bag you need to run faster than the wind blows, otherwise the bag will keep getting farther and farther away, never to be caught.

If the goods, services and lifestyle that you seek are inflating in price faster than your ability to buy, then you will never achieve your goals. They will perpetually be beyond your reach, never to be caught.

If the prices you care most about are exactly what is measured in the CPI’s basket, and in the exact weighting proportion, then your inflation rate is exactly the CPI. For the past year, the cost of everything you want to buy rose by 7.5%. However, if you aspire to home ownership, higher-education, vacation time, passive income, retirement, and wealth, then your inflation rate was higher. The cost of a better life, less stress, more free time, and more prosperity is moving faster and farther, much like the bag blowing in the wind.

Unless your ability to acquire the items you care most about is keeping pace, you will never get there. The bag will get farther and farther away.

The fact that the CPI increased at a rate not seen in 40 years illuminates the worrying trend of the rising costs of living, but for those who seek to improve their lives, they must look beyond such a limited basket.

Your inflation rate may be much higher than you think.